Lesley Russell writes:

Australian news outlets are this week full of stories about the drought crisis, while in Europe, the United Kingdom and the United States summer temperatures are scorching and wildfires burn out of control: small wonder climate change is on our minds. An article on the Northern Hemisphere’s “savage summer” in Croakey highlights the issues.

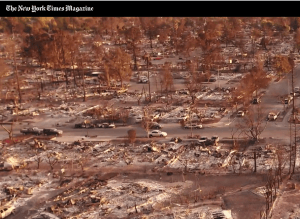

There’s a great summary of international climate change issues here at The New York Times, and the August 1 issue of the New York Times magazine (see photo, right) has an amazing article and photos on the ten-year period, from 1979 to 1989, when scientists first came to a broad understanding of the causes and dangers of climate change.

There’s a great summary of international climate change issues here at The New York Times, and the August 1 issue of the New York Times magazine (see photo, right) has an amazing article and photos on the ten-year period, from 1979 to 1989, when scientists first came to a broad understanding of the causes and dangers of climate change.

As the introduction says:

“It will come as a revelation to many readers – an agonizing revelation – to understand how thoroughly they grasped the problem and how close they came to solving it.”

There has been a considerable focus on the impact that climate change will have – and is already having – on health, but too often the mental health impacts are ignored or they are seen only as issues when there are environmental disasters and extreme weather events. Some recent papers explore the long-term implications of global warming for mental health and wellbeing.

Climate change and mental health

More than extreme weather

A 2008 report from the WHO Regional Health Forum predicted that climate change would have a significant impact on mental health in the South East Asia region. While extreme weather events also play a role, it is known that rising temperatures and humidity are associated with increases in Emergency Department visits for mental health concerns, that hospitalisation rates for schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders are increased in warmer weather, and that suicide rates increase as temperatures rise.

Earlier this year Nature Climate Change devoted a whole issue (see cover, right) to the different ways that climate change can impact mental health. The introductory editorial said:

Earlier this year Nature Climate Change devoted a whole issue (see cover, right) to the different ways that climate change can impact mental health. The introductory editorial said:

“It is not that climate change is causing new classifications of psychiatric disorders, but rather that it exposes people to circumstances that aggravate known risk factors. … Climate change can also create situations that disrupt treatment of existing conditions. For example, displacement can interfere with access to medication, and some psychiatric drugs are rendered ineffective by extreme heat or exacerbate heat-related health problems because they interfere with the body’s ability to thermoregulate.”

Climate change and suicide

A very recent publication quantifies the link between climate change and suicide in the US and Mexico. It found that suicide rates rise 0.7 percent in US counties and 2.1 percent in Mexican municipalities for every 1°C increase in monthly average temperatures. This effect is similar in both hotter and cooler regions of the two countries and has not diminished over the time period studied, indicating limited adaption to rising temperatures.

The authors project that unmitigated climate change could result in a somewhere between 9-40,000 additional suicides across the US and Mexico by 2050. That’s a change in suicide rates comparable to the estimated impact of economic recessions or gun restriction laws.

This paper is seminal because it makes a causative claim about high temperatures and the increase in suicides. The authors have controlled for every other major variable that might affect suicide rates.

Knowing that the Indian sub-continent has been experiencing a significant warming trend, I went looking for suicide data from India. The country has experienced a 23 percent increase in the suicide rate over the years 2000-2015. A 2017 publication, using five decades of data, indicated that 6.8 per cent of the total upward trend in suicides (some 59,000 lives) is attributable to an increase in temperatures. This was quantified as: for average temperatures above 20°C, a 1°C increase in a single day’s temperature causes approximately 70 suicides. Things will get much worse – India’s average temperatures are expected to rise by another three degrees by 2050.

Australian research has shown that in Sydney and Brisbane, when the difference of the monthly average temperature in one month compared with the previous one month increased by 1°C, there was a three per cent increase in suicide in these cities.

Drought-related stress

A paper in this week’s Medical Journal of Australia looks at the drought-related stress experienced by NSW farmers, their families and communities. It used data from the Australian Rural Mental Health Study collected during 2007–2013, a period that included the Millennium Drought (1997–2010), which caused severe environmental, social, and economic losses.

The study found that drought related stress was most frequently reported by farmers who were younger (aged under 35), who both lived and worked on a farm, were experiencing greater financial hardship, and were in outer regional, remote or very remote areas.

The findings underscore not just the importance of access to mental health services, but also that employment and social networks are protective factors for farmers in drought-affected areas. A particular barrier is that drought has been linked to reduced help-seeking behaviour, due to issues such as financial strains, perceived stigma and rural stoicism.

This week the NSW state government announced an additional $500 million assistance package for the state’s farmers (with some $600 million provided earlier in the 2018 NSW Budget, this takes the total to around $1 billion). The media release says this new package also includes funding for mental health and counselling, but the nature of this is unspecified and it is not clear if it is in addition to the funding already provided.

Is this enough? And where will the rural mental health workforce come from? (I wrote about the mental health workforce shortage in a recent Health Wrap.) One recent news article described the mental health of people in affected communities as “critical”, with some people at the brink of suicide.

Inaugural professor of climate change & mental health

Did you know that in October 2017 the University of Sydney’s School of Public Health appointed Professor Helen Berry as the inaugural Professor of Climate Change and Mental Health?

You can access her publications here. It is particularly welcome to see that her work includes the impact of climate change on Indigenous communities (If the land’s sick, we’re sick. The impact of prolonged drought on the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal communities in rural New South Wales)

Super Saturday health commitments

The recent Super Saturday elections saw a raft of commitments from the major parties in health.

Liberal/National Party pledges:

Braddon: mental health services $4.8 million, medical research centre $2.4 million

Longman: drug rehabilitation services $11.1 million

Mayo: 12 aged care beds $3.9 million, mental health services $1.2 million

Labor pledges:

Braddon: elective surgery fund $30 million, travel for health services $4.5 million, TAFE hospital training $0.8 million, extra Centrelink staff – 20 to Medicare

Longman: Bribie Island urgent care clinic $17 million, Caboolture hospital $2.9 million, Hospital chemotherapy clinic $10 million, TAFE hospital training $1.5 million

Fremantle: hospital urgent care $5 million

The Turnbull Government’s messaging hewed substantially to their “jobs and growth” mantra, but there was scepticism about its claims that company tax cuts would lead to improvements in business investments and jobs. This was particularly so in Tasmania, where company tax cuts were portrayed as handouts to the big banks.

The Government’s determination to avoid accusations of failing to support Medicare saw a strong defence of its record on health spending, with Turnbull claiming “we are spending record amounts on hospitals, we are spending record amounts on health”.

That claim was subject to an RMIT ABC Fact Check. The decision: the claim is largely correct but not very meaningful, as health funding “will inevitably be record spending if it’s keeping pace with need”. Turnbull attacked Labor and Opposition Leader Bill Shorten for “lying” about cuts to health, saying that Commonwealth government funding for the Caboolture hospital had increased.

That claim was subject to an RMIT ABC Fact Check. The decision: the claim is largely correct but not very meaningful, as health funding “will inevitably be record spending if it’s keeping pace with need”. Turnbull attacked Labor and Opposition Leader Bill Shorten for “lying” about cuts to health, saying that Commonwealth government funding for the Caboolture hospital had increased.

It was disappointing that both sides of politics once again resorted to hospital funding as their key health commitments. While the voting public is always concerned that their public hospitals are well resourced, they recognise that there are other important health and healthcare needs.

“The economic disconnect” in health

It is interesting to read on the Super Saturday campaign and results in light of the findings of the recently released Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) report Community pulse 2018: the economic disconnect which looks at the results of polling to explore Australians’ attitudes to work, education, health, community and the economy.

The report highlights the extent to which voters’ thinking on the economic disconnect is well ahead of that of politicians: 79 per cent of people believe that the gap between the richest and poorest Australians is unacceptable.

The top five issues that matter most to people personally are:

- Reliable, low-cost basic health services.

- Reliable, low-cost essential services.

- Access to stable and affordable housing.

- Affordable, high quality chronic disease services.

- Reduced violence in homes and communities.

People see the five critical national issues as:

- High quality and accessible public hospitals.

- Strong regulation to limit foreign ownership of Australian lands and assets.

- High quality and choice of aged care services.

- Increased pension payments.

- Tough criminal laws and criminal sentences.

These societal concerns around healthcare and the social determinants of health are not substantially reflected in the current political rhetoric. Let’s hope they rise to the top as the next federal election approaches.

New reports on primary care

AIHW report on GP coordination of care

Last week the AIHW published on the MyHealthyCommunities website a report Coordination of health care – experiences with GP care among patients aged 45 and over, 2016. The report presents findings from the 2016 ABS Survey of Health Care at the Primary Health Network (PHN) level, as well as variations in the use of and experiences with GP care by socio-demographic groups.

There’s good news: in 2016, almost all patients aged 45 and over (98 per cent) had a usual GP or a usual place of care and 80 per cent had both a usual GP and place of care. However, there are inequalities and divides: patients were more likely to have a usual GP or place of care if they lived in major cities, spoke English at home, had higher levels of education, and had private health insurance.

There’s good news: in 2016, almost all patients aged 45 and over (98 per cent) had a usual GP or a usual place of care and 80 per cent had both a usual GP and place of care. However, there are inequalities and divides: patients were more likely to have a usual GP or place of care if they lived in major cities, spoke English at home, had higher levels of education, and had private health insurance.

Patients reported generally positive experiences of care from their usual GP or place of care, but there was variation across PHN areas. Only 71 per cent of patients in Western Queensland rated their care as excellent or very good, compared to 87 per cent in Eastern Melbourne, Western Victoria, Brisbane North and Gold Coast. Patient experiences were similar across the different types of usual place of care, including GP clinics, community health settings, and Aboriginal Medical Services.

And there’s a further downside: while patients were more likely to have a usual GP and place of care if they reported having poorer health and more long-term chronic conditions, these patients also reported less positive experiences with their care. The report does not explore why this is so, but possible reasons include lack of care coordination, a sense that doctors are too busy to take time to explore patients’ needs and concerns, and a failure to see improvements in health status.

Grattan Institute report on mapping primary care

Some of the issues raised in the AIHW report discussed above are teased out further in the report from Stephen Duckett and Hal Swerrison released this week by the Grattan Institute. Mapping primary care in Australia looks at the barriers many Australians, especially the poor and the elderly, face in getting the best possible health care – not just access to doctors (both GPs and specialists), but also allied health services, pharmacists and dentists.

The report finds that the funding, organisation and management of primary care has not kept pace with changes to disease patterns, the economic pressure on health services, and technological advances. In particular, primary care services are not organised well enough to support integrated, comprehensive care for the 20 per cent of Australians who have complex and chronic conditions.

It spells out in sharp terms the inequalities we already know:

- Australians’ access to GPs and specialists varies according to their wealth.

- About one in five Australians do not get the recommended level of oral health care.

- Access to allied health services such as physiotherapy and podiatry varies significantly according to where people live.

The report calls for:

- A comprehensive national primary care policy framework to improve prevention and patient care.

- Formal agreements between the Commonwealth, the states and Primary Health Networks to improve management of the primary care system.

- New funding, payment and organisational arrangements to provide better long-term care for the increasing number of older Australians who live with complex and chronic conditions, and to help keep populations healthy in the first place.

Wither primary care reforms?

The push to address the increasing erosion of universality in Medicare and to reform primary care/general practice grows, even as politicians continue to make election promises around hospital funding.

Meanwhile, there are grassroots efforts to fill in the policy gaps. This week I attended a roundtable hosted by the Consumers Heath Forum (CHF), the George Institute for Global Health and UQ-MRI Centre for Health System Reform and Integration that looked at:

- Defining and considering the challenges and opportunities along the way to drive real, lasting change and innovation in primary care.

- Ways to fast track transformation of primary care.

- The realistic steps we can take to identify and overcome barriers.

- What various players in the health system require to reach the finish line.

As the Stimulus Paper for the roundtable stated: we have been talking about better integrated care for consumers for more than 20 years, what are the major barriers to really making it happen?

Health Care Homes, once seen as a game-changer, are now described by the Health Minister, Greg Hunt, as “an interim step”. The 2.0 version is probably not even a work in progress – Hunt has said he will “nut out the details with the MBS Review, the RACGP and the AMA” (note that consumers and patients are not mentioned).

The CHF has called for a strong primary health care system to be the central focus of all political parties at the next federal election. Let’s hope political leaders and strategists are listening.

Lessons from Appalachia?

A recently released set of resources from the Appalachian Regional Commission (a regional economic development agency that is a partnership of federal, state and local governments for the 13 Appalachian states in the US), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky takes a fresh approach to understanding health in Appalachia by focusing on community strengths and identifying local factors that support a Culture of Health.

[The Appalachian Region includes all of West Virginia and parts of 12 other states: Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. The Region is home to more than 25 million people, 42 per cent of whom live in rural areas. Appalachian incomes, poverty rates, unemployment rates, postsecondary education levels and health outcomes lag well behind those of the nation as a whole. See the report on health disparities here.]

These resources include:

- Case studies of ten “Bright Spot” counties with better-then-expected outcomes in health.

- The performance-focused research methodology that helped identify these counties.

- healthinappalachia.org – a website that explores extensive county-level data for the entire region.

I’m struck by how useful and engaging this approach might be to tackling health disadvantage in Australia. An approach that identifies and builds upon communities’ strengths and successes is so much more useful and progressive than the deficits-based approach to reporting that dominates much of the work here.

Several cross-cutting themes were identified from the Bright Spots:

- Community leaders engaged in health initiatives.

- Cross-sector collaboration.

- A tradition of resource sharing.

- Local healthcare providers committed to public health.

- Active faith communities grassroots initiatives to combat substance abuse.

People are recognised as the greatest asset for Bright Spots. They generate collective pride and power through volunteerism, community commitment, and shared values. Bright Spot counties also benefit from “anchor institutions” such as schools, businesses, churches and hospitals that work to improve community health and the social factors that affect it.

I would be interested in commentary on this approach from those who are working in disadvantaged communities in Australia, whether rural, regional, remote or urban.

Croakey is always delighted to highlight Australian Bright Spots.

The future of My Health Record?

You might notice the absence of commentary here about the problems (or should I say debacle?) over My Health Record. I’ve stayed from this topic simply because it has been covered off so well, in all its aspects, by others.

Here’s just a partial list:

- Marie McInerney and Tim Woodruff in Croakey https://croakey.org/health-minister-bows-to-privacy-pressure-on-my-health-record-but-big-issues-remain/?mc_cid=6c0af06da6&mc_eid=6c83a37172

- Peter Bragge and Chris Bain in Croakey https://croakey.org/opting-out-of-my-health-records-heres-what-you-get-with-the-status-quo/?mc_cid=6c0af06da6&mc_eid=6c83a37172

- Jim Gillespie in The Conversation on the case for opting in https://theconversation.com/my-health-record-the-case-for-opting-in-99850

- Katharine Kemp and legal colleagues in The Conversation on the case for opting out https://theconversation.com/my-health-record-the-case-for-opting-out-99302

- A summary of articles in The Conversation on My Health Record https://theconversation.com/us/topics/my-health-record-22162

- An analysis by the Australian Parliamentary Library showing that MyHealthRecord could be accessed by police was pulled from the internet but later reappeared in a modified form.

- The 2016 evaluation of the (opt in) participation trials for My Health Record is here.

It is not yet clear what changes the Government will make to the current My Health Record legislation, what the timetable is for this, and whether the current opt-out period will be extended or suspended until such changes have been made.

ICYMI: Reading and resources recommended by the Croakey team

The interim report from the Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/reportjnt/024174/toc_pdf/Interimreport.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf

The interim report from the Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/reportjnt/024174/toc_pdf/Interimreport.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf- The New South Wales Coroner’s report into the death of Courtney Topic: “Her death raises broad issues about how police officers are trained to deal with people suffering a mental health crisis. Background news coverage here: https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/errors-were-made-shooting-death-of-courtney-topic-by-police-was-preventable-coroner-finds-20180727-p4ztzk.html

- Queensland Coroner’s report into the death of Iranian asylum seeker Hamid Khazaei, who died after suffering severe sepsis from a leg infection on Manus Island: https://www.courts.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/577607/cif-khazaei-h-20180730.pdf

- Beyond the Pale: Cultural Diversity on ASX 100 Boards

Treespond: a campaign that allows users to sponsor the planting of a tree in response to US, such as: “…we need some global warming, it’s freezing”.

Treespond: a campaign that allows users to sponsor the planting of a tree in response to US, such as: “…we need some global warming, it’s freezing”.- Australia’s drought: the cancer eating away at farms: An interactive photo essay from Reuters photographer David Gray, from Walgett.

- Previous editions of The Health Wrap can be read here.

- Croakey thanks and acknowledges Dr Lesley Russell for providing this column as a probono service to our readers. Follow on Twitter: @LRussellWolpe